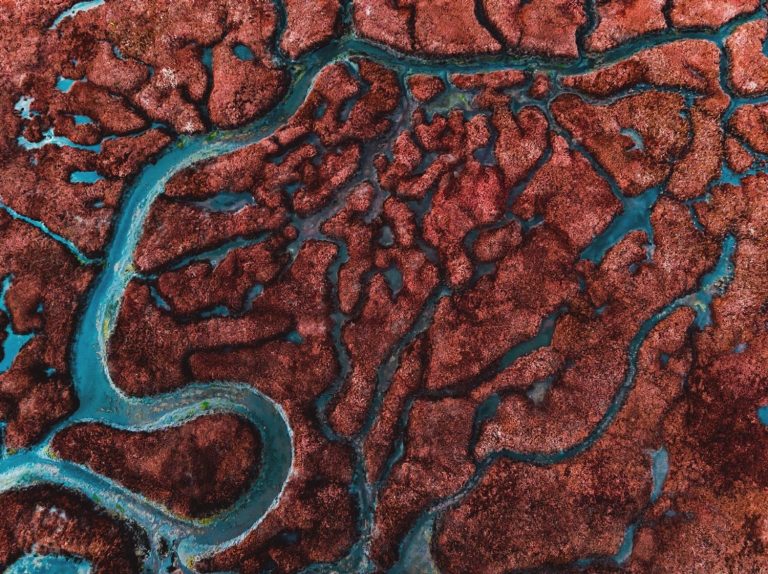

As the world population increases and economies progressively rely on linear (rather than circular) production to meet their demand for energy, water and food among others, companies have been under enormous pressure to find resources and accommodate waste and emissions. Although, only a small share of the total is reused or recycled as secondary materials, leaving the vast majority, which includes valuable and scarce resources, being designated to landfill or incinerated.

Circular public procurements are an alternative to this outcome, aiming to keep products in the value chain for a longer period and to recover raw materials after each consecutive use. Public procurement refers to the process by which public authorities, such as regional and local authorities, seek to purchase works, goods or services from companies under various commitments, for example with the intention to reduce environmental impact throughout the product life cycle.

To do so it is mandatory looking beyond short-term needs and consider the longer-term impacts of each purchase, even by questioning whether it should be made at all. This approach recognises the role that public authorities can take upon in supporting the transition towards a circular economy. Circular procurements seek to contribute to closed energy and material loops within supply chains, whilst minimising environmental impacts and waste creation. The EU Action Plan for the Circular Economy adopted by the commission in March 2020 acknowledges public procurements as the key driver in the transition towards a sustainable, low carbon, resource efficient and competitive economy.

The Implementation of Circular Procurement

The implementation of circular procurement can take effect at different levels based on the model adopted:

- At the ‘system level’, which concerns the contractual methods that the purchasing organisation can use to ensure circularity. It ranges from supplier take-back agreements, where the supplier returns the product at the end of its life in order to recycle, remanufacture or refurbish, and re-use it.

- At the ‘supplier level’, in which suppliers can build circularity into their own systems and processes, in order to meet circular procurement criteria. And;

- At the ‘product level’, focused solely on the products that suppliers to public authorities may themselves procure further down the supply chain.

The introduction of circular procurement should answer to issues posed by the products, services or departments it applies to and what targets, priorities and timeframes are in place, and how these are monitored. A logical first step in becoming more circular is identifying elements of procurement practices that require a change of thinking in order to shift to circular models and the practices include. For example, often the need revolves around not a specific product, but the function it provides, thus product service systems allow suppliers to pool products to satisfy more customer needs with fewer units, thereby reducing the environmental impacts of production.

As opportunities arise, it may be helpful to introduce the change gradually at first. This can provide information to test approaches and examples to other departments, making a full roll-out at a later stage more appropriate. Moreover, costs incurred during use (such as energy consumption, service and maintenance costs) may be highly significant in terms of price. Due to the possibility of different budgets for upfront costs of purchase and long-term maintenance, cross-departmental cooperation is often essential.